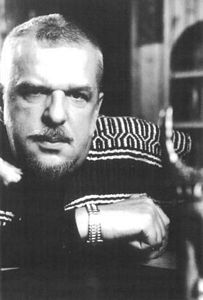

Gil

Brewer

noir fiction writer |

|

She wasn’t what you would call beautiful. She was just a red-haired girl with a lot of sock. She stood behind the screen door on the front porch, frowning at me. "I’m Jack Ruxton " I said. "From Ruxton’s TV. Sorry I’m late." "That’s all right." She was maybe seventeen or eighteen. The porch light was on. It was about eight o’clock on a Monday night. Looking past her, I could see through a long, broad living room, expensively furnished, and on into a brightly lighted bedroom. A man with iron-gray hair lay on a hospital bed under a sheet, with his toes sticking straight up. His head was flung back as if he were in a cramp. There was a lot of tricky-looking paraphernalia, rubber hoses and tanks and stuff, beside the bed. A fluorescent bedlight glared across his face. It was eerie. "Well," I said. "TV on the blink?" "No. That’s not what I called you for, Mr. Ruxton." She caught on that it was uncomfortable with the screen door between us, gave it a shove with her knee. I backed away on the porch. She stepped out and closed the door. "I’m Shirley Angela," she said. I nodded. She had on a red knitted thing, made of one piece. It was shorts and a top, without sleeves. The top was what I think they call a boat-neck, tight up against her throat. The whole thing was very tight on her. Her face seemed almost childlike, but she was no child. She said, "Let’s go out back and talk." "Okay." "He’s sleeping. He only sleeps a few minutes. It might wake him if we went in now." "Okay." She brushed past me and walked down the sloping cement ramp built from the top of the porch to the front walk. There were no steps. The ramp was for wheelchair cases. I followed her. The hair was shoulder length, and more auburn, close up. Her waist was extremely narrow. She walked on the balls of her feet, throwing her hips out in back; it was there to be looked at, and she must have known it. "Out here, Mr. Ruxton." I grunted, and we came around the side of the house on a path of stepping stones. She could really do things on stepping stones. She flipped a switch on a pine tree, and floodlights came on out in the yard. We walked along that way, playing Indian, to where the path ended. She paused, but didn’t turn, and said, "There are just the two of us living here. I have to take care of everything." Then she moved off again. I didn’t say anything. The lot was a big one, maybe two hundred by three hundred. It was wooded with Australian pine, a couple of big old water oaks, and royal palms. You could see soft lights in a house beyond a hedge next door. There was a sea wall down there by the Gulf, and the moon and floodlights gleamed on the water. Three weathered lawn chairs stood around a rusting steel-topped table that had once been white. "We can sit out here," "Okay." We moved the chairs away from the table and sat. I didn’t know what we were waiting for, but neither of us said anything for a minute or two. You knew she was young, yet there was something contained about her. She was almost serene. Her skin was pale, almost pure white. Her face was smooth and oval, but with high cheekbones under the velvety skin. Looking at her, you knew it would be something to lay your hands on that soft white skin; very smooth, like a breast, all over. The thought did occur to me: What the hell is she doing here alone with that old guy in the bed? And somehow I knew it wasn’t any money problem. That’s all I thought, though. I decided to let her carry the ball, and quit thinking how good she looked. Grace had looked good, too, and now she had me half nuts, the way she was acting. We had had it good and then lost it, and now she wouldn’t let me alone and I couldn’t shake her. It made me half sick every time I thought of Grace. I didn’t know what the hell to do about her. "Florida’s sure nice, nights like this," I said. "That’s a fine breeze. Smell the salt?" "Mr. Ruxton. It’s really going to entail a lot of work—what I want done." Her voice was much like her face. It seemed kind of flat and childish at first, until the overtones hit you. She leaned forward and spoke earnestly. "We have only one television set, a small one. One of these cheap seventeen-inch portable models. It’s just no darned good, what with those dog ears they use." "Rabbit ears," I said. "If the set’s any good, you should have decent reception. Of course, out here on the beaches, you might have some interference. I’ll check into that." "Yes. But what we want are two large sets. Color. One for the living room, and then I want one suspended over his bed, so he can watch it in bed, you see?" "Hm-m-mmm." "He’s able to get up, of course, when he feels well. But mostly he’s in bed, lately. It would be best to hang it right over his head. So he could see it easily." She leaned back and folded her hands in her lap. "We’d pay cash, of course," she said. "You don’t have to worry about that." "Wasn’t worrying." She smiled briefly. "Think I can handle everything you want, Miss Angela." "And, also—a good antenna." "Okay." "That’s not all. I want one of these intercom businesses set up, too. Between all of the rooms. So he can call me whenever he needs me. Sometimes he needs me in a hurry. His voice isn’t too strong." "We can take care of that." "I have no idea which brand is best. I used to read these consumers’ reports, but I don’t keep up anymore. Naturally, Victor—Mr. Spondell, that is—doesn’t care, so long as everything works perfectly. He’s particular about buying the very best, though." "I understand." She was a puzzler. I knew she was in her teens, yet she had that direct and deadly poise of a woman beyond her years. I was figuring Miss Shirley Angela was going to help my business in her own small way. This looked like a good deal. You’ve got to whittle every stick you get your hands on, if you expect to be big. Your business has to be the biggest and the best, if you expect it to pay off. That’s how it was going to be with me. There was the new annex, and two new trucks, and two new men. I was plenty in debt. But if you’re smart enough to find all the angles and ride them down, you won’t drown. In the beginning, you’ve got to scramble, and you’ve got to ride those angles hard, every damned one of them. You don’t let any of them throw you, not even the measliest, because every buck adds up. Either that, or you make it big and fast some way, and quit cold. I had learned the hard way, misfiring across a lot of lousy years, that I would have to slug for it—slug everybody in sight. So I was glad I’d come out here myself, instead of sending one of the men from the shop. It had been mostly by chance, and because Grace was hanging around again outside the store. I decided to hold off the pitch till after we were inside the house. From the way it looked, the guy in there wouldn’t be any hindrance. Things seemed a little strained, though, and I wasn’t sure why. I kept wondering what her relationship was to the guy in there. "We can go in now," she said. "He’ll be awake." We walked back the way we had come and went into the house. As we entered the living room she said, "I’ll let you decide the best place for everything, Mr. Ruxton. You’ll know best, I’m sure." We left his room until last. She was avoiding it, and trying every way she knew to make it look as if she wasn’t avoiding it. I wanted to get a good look at him, and that room. Her acting the way she did only made it worse. The room was like a magnet. It was a fairly large house: large living room, three bedrooms, dinette, kitchen, three bathrooms, and a sprawling glassed-in area they call a Florida room down here. It was so quiet you could hear him clear his throat, or change position on the bed. I couldn’t keep my eyes off her legs and she knew it. We were in the kitchen when she excused herself and came back in a minute buttoning up a yellow housecoat. "What do you think, Mr. Ruxton?" "Well, there’ll be a few minor difficulties in the wiring, but we’ll iron them out. Maybe I’d better have a look in there, now." She turned quickly away. "All right." We went into his bedroom. "Victor?" He opened his eyes and stared at me. "Victor, this is Mr. Ruxton. He’s come to put in the TV sets and everything. Like we talked about. He wants to check your room." He blinked, just once, staring at me. Those blue eyes were really sharp. Somehow they reminded me of an eagle’s I’d seen in a Belgian zoo. It was as if he stared at the wall right through your head. "Good," he said. "That’s good." His voice wasn’t strong. He had finely drawn features, a long nose, and heavy brows knotted with snarled gray hair. There was a quality of stubborn arrogance in his glance, of tired determination. The hair on his head was iron-gray, and like barbed wire. He looked as if he were grinning, but it was only the shape of his mouth when relaxed. He wore light gray pajamas. The sheet was neatly drawn and folded across his chest, his hands folded on the sheet. He was a shell, but looked as if he’d once been as strong as an ox. The sound of his normal breathing was bad. Something like a horse with an advanced case of the heaves. "Ruxton, eh?" he said, breathing like wind in an October com field. "The only Ruxton I believe I ever had the pleasure of becoming acquainted with was an unmitigated ass and a dirty son of a bitch. You any relation to him?" I watched the hands shake; big, once-powerful hands, folded on the sheet. "Probably," I said. Some gut-wrung breathless sounds burst past his lips. He was laughing. I knew then I wasn’t going to make any pitch to her for anything. I would do my job and get out of here. I didn’t like the guy. "Victor," she said, moving quickly to the side of the bed. "Please, take it easy, will you?" "Oh, Christ," he said. He spoke with soft pain. She glanced at me, her eyes up-flung in a show of resignation, and began straightening his pillows. There were oxygen tanks beside the bed, standing upright in a nickel-steel rack with wheels and handles. A long black coil-rubber hose and mask dangled over one side of the gleaming handles like an eyeless python with its mouth open. The room was antiseptically clean, neat and white. Not even a magazine or a chair. Just the hospital-type bed and the oxygen tanks. To the left a white-curtained window opened on the side of the house, over the path that led out back. Another window was at the head of the bed. Hanging on a bedpost by a black ribbon was a small, filigreed silver bell; the kind that used to sit on the back of the buffet at your grandmother’s house in the long ago of your early childhood. I stared at the ceiling over the bed, trying to make it look as if I were doing my job. You think about hanging TV sets on the ceiling, only you just don’t do it. "I’ll have to check the attic rafters," I said. "All right," she said. I looked at him again. He didn’t seem too well. I went over to the bedroom door, and she came along, and we stepped into the living room. The housecoat was coming unbuttoned. She watched my eyes. "He’s very bad off," she said. "How do I get into the attic? You have a flashlight?" "Yes—" The sound reached me faintly from the bedroom. A butterfly brushed a broken wing against the silver bell. "Shir-LEY!" It was Death croaking. She gave me a quick look and hurried back into the bedroom. I watched her. He writhed on the bed, his mouth open, hands clenching the sheets. He was trying to breathe. "Would you please help me?" she said. I went in there. "Turn that handle wide open. Yes, that’s it." She leaned on him, holding one arm down, and mashed the mask over his nose and mouth and I turned it on. It was life pumping through the rubber hose. I looked away and tried to think of something else so I wouldn’t hear him. In a minute or two she said, "You can turn it off now." I turned it off. She came around and draped the black rubber hose over the handle. He lay there with his eyes closed. Sweat had formed in splotches on his face and hands. "Thanks, baby," he said. He didn’t open his eyes. She made a soft purring sound in her throat, and moved to the other side of the bed, straightening the sheet. I watched her and she looked up at me. I caught the expression on her face. It told me a lot. We watched each other across the bed. She knew I’d seen what she was thinking. It was as if the bed were suddenly empty. He just wasn’t there. She jerked her gaze away and walked out into the living room. I followed, seeing his feet sticking straight up under the sheet, from the corner of my eye. I’d once done apprentice work for an undertaker and had seen a lot of feet like that. "Sorry you had to see him that way," she said. "Forget it. Glad to help. Where’s that flashlight?" She went to the kitchen and returned with a five-cell job. I stood on a chair and swung up into the attic through the closet in her bedroom. I checked the rafters. I couldn’t get him out of my head. He was ]ust like a corpse, only he still breathed and he was still king. I came back down. "Sure," I said, handing her the flashlight. "It won’t be too difficult, fastening a TV set to the ceiling." "I suppose you’re still concerned about what happened, aren’t you, Mr. Ruxton. I shouldn’t’ve asked you to help. I know how disturbing something like that can be, seeing it for the first time. I just forgot, I’m so used to it." \ I thought, Honey, you’ll never be used to that. She must have seen something in my eyes. She spoke quickly. "It’s a respiratory ailment. Very complicated. It gets more complicated all the time." She stared toward his room. "Degeneration," she said. "He’s been to the finest specialists in the country. Luckily, he’s very wealthy." She looked at me again. "It’s his lungs, his throat, bronchial tubes—and now, his heart, too. He’s—we, that is, have lived everywhere, but he likes it here best." "You’re his nurse, then." "He’s my stepfather, Mr. Ruxton. But I suppose you could say I was his nurse. I’ve been taking care of him ever since he sold the business. He manufactured expensive furniture. All kinds. Surely you’ve heard the name Spondell? Very likely some of the television cabinets you sell were designed by Victor." His name might as well have been Xshdkgteydh, for all I’d ever heard of him. I said, "Yeah. The name does seem to ring a bell, at that." She didn’t speak, so I said, "How old are you, anyway?" She looked at me along her eyes. "Eighteen." She paused. "He insisted I take care of him—like this." "Shouldn’t he be in a hospital?" She gave a little jerk with her head, and sighed. "That’s just it. The doctors think so. And now Doctor Miraglia claims it’s very important. Victor just tells him ’Bosh!’ and refuses to go." "Who’s this Miraglia?" "He’s Victor’s doctor now. Victor won’t let anyone else come near him. He thinks Doctor Miraglia’s the finest doctor in the world." She sighed again. "Everybody thinks Victor should be in the hospital." "Who’s everybody?" "I mean, before we came here." "What do you think?" She smiled. It didn’t mean a thing to me, because she’d pushed the whole business much too far. You get to meet a lot of people, and you know how they react when you first meet them. There was only one reason why she’d tell me all this. Maybe two reasons, but I figured I was crazy, thinking the other one. She said, "Let’s discuss something else. This must be tiresome to you." "No relatives?" "What?" "Him. Hasn’t he any family of his own? I mean, other than you?" She turned and moved to a broad cocktail table beside a long, low pale blue couch. She laid the flashlight on the table. "Nope," she said. "Nobody but me." She turned and looked at me, smiling. "Suppose I drop around tomorrow morning?" I said. "I’ll bring some stuff along. We can decide what you want. How’s that?" "All right. That’s fine." "If we started anything tonight, we’d never get finished." "I suppose you’re right." We walked across the room. I stepped out onto the front porch. I looked back at her through the screen. "Good night, Miss Angela." "Good night, Mr. Ruxton." Copyright © 1958 by Gil Brewer.

|

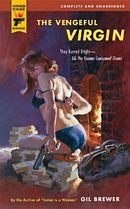

THE

VENGEFUL VIRGIN

Gil Brewer

©

1950-2022 Gil Brewer Estate

Site Map

Links of note:

STARK HOUSE PRESS Needle - Mag of Noir Hard

Case Crime therapsheet

Mystery

File George

Tuttle Fantastic

Fiction